Enniscorthy

My day trip to Enniscorthy began at Vinegar Hill, site of a decisive battle in the 1798 Rebellion.

More than 12,000 rebel fighters gathered at the rocky outcropping and Norman tower that sit above Enniscorthy. They were surrounded by more than 13,000 forces loyal to the King (English dragoons, Hessian regulars, Irish militias). The rebels were mainly armed with pikes--a metal spear on the end of a long wooden handle. The English forces had musket rifles and canons. Complete slaughter was avoided by the failure of one English general’s troops to arrive in time to complete the circle of troops ringing the rebels. While many of the rebels escaped, more than 1,000 women and children were raped and killed on the hill.

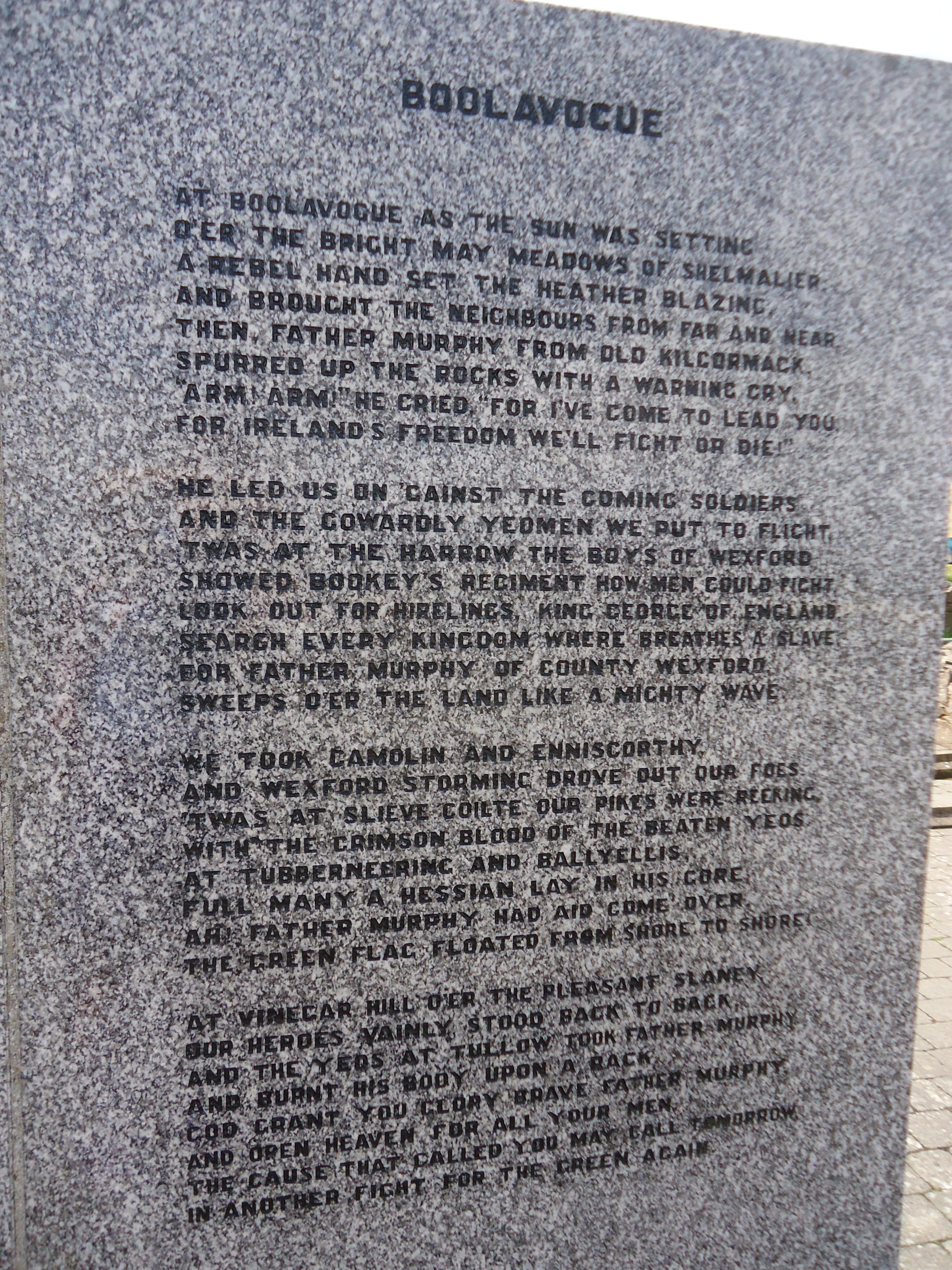

This famous ballad celebrates one of the two priests who led the rebels--both executed after Vinegar Hill. More info here.

And this is the peaceful view from the car park.

I got this shot by standing on a tall iron bollard as I descended the hill into Enniscorthy, with Enniscorthy Castle on the left.

Here’s one of the bridges over the River Slaney in Enniscorthy.

Here’s a quaint street:

I didn’t know this was a thing.

A view of the castle:

The tour of the 12th century Norman castle was a bit weird. It was last occupied by the Roche family, from 1903-1953. Their factories turned barley into malt, which they sold to the Guinness factories.

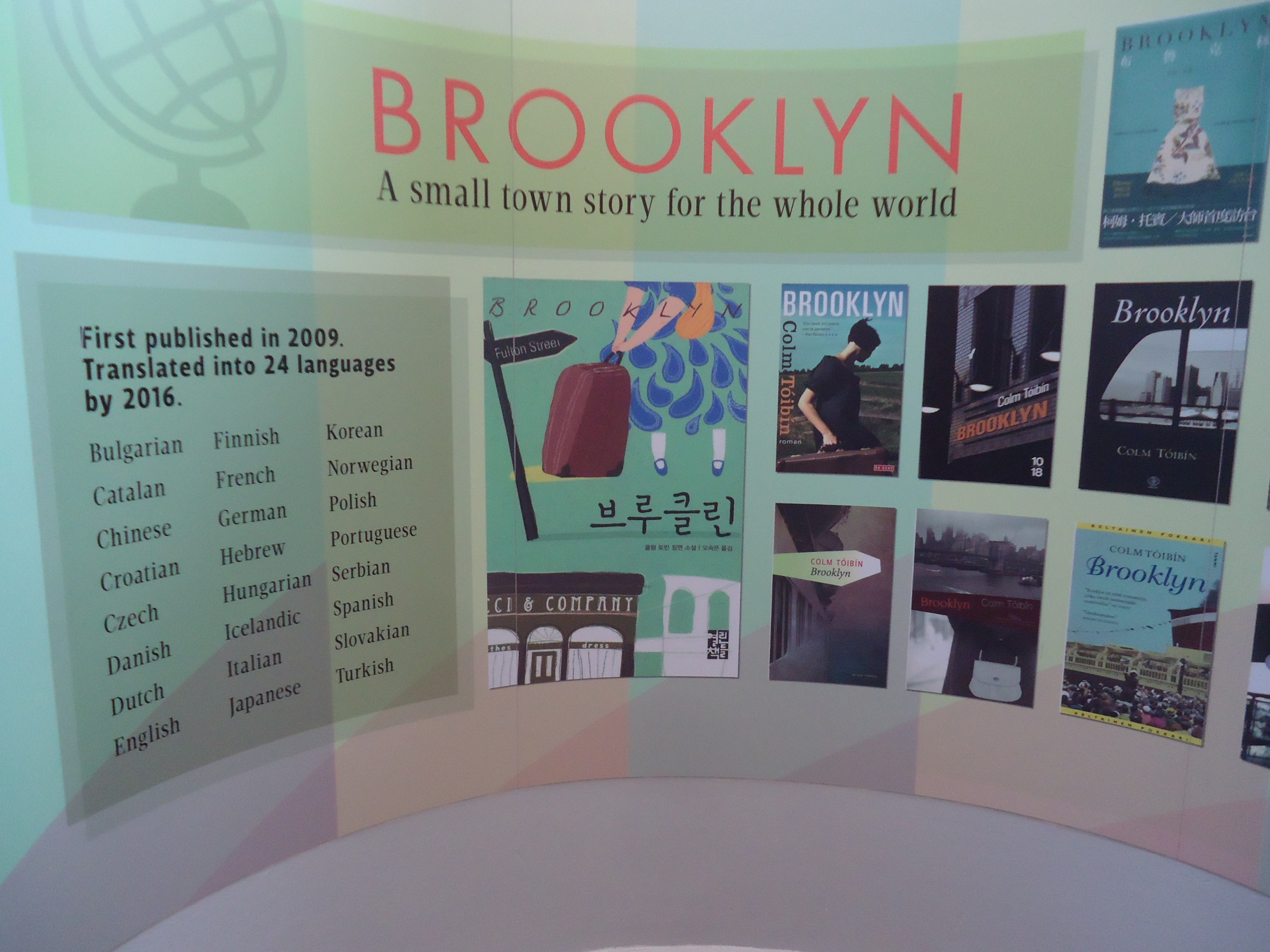

So the exhibits focused on: the filming of Brooklyn in Enniscorthy; Eileen Gray, an architect famous for her 1920s modernist style; and posters showing what the house might have looked like when the Roches lived there. In other words, anything but the approach used by the National Trust: faithfully represent, in painstaking detail, a property’s history.

Book covers for Brooklyn in different languages:

The film played on a loop if you wanted to watch it.

Here’s the Eileen Gray room:

Her chair modelled on the Michelin Man:

Here is a room partially furnished as it might have been in the 50s:

And here are photos of what it would have looked like when lived in:

While the castle served as a prison during the 1798 Rebellion, I had to go to the 1798 Rebellion Centre, a nondescript building on the edge of town, to learn more about this pivotal event in Ireland’s history. Big mistake.

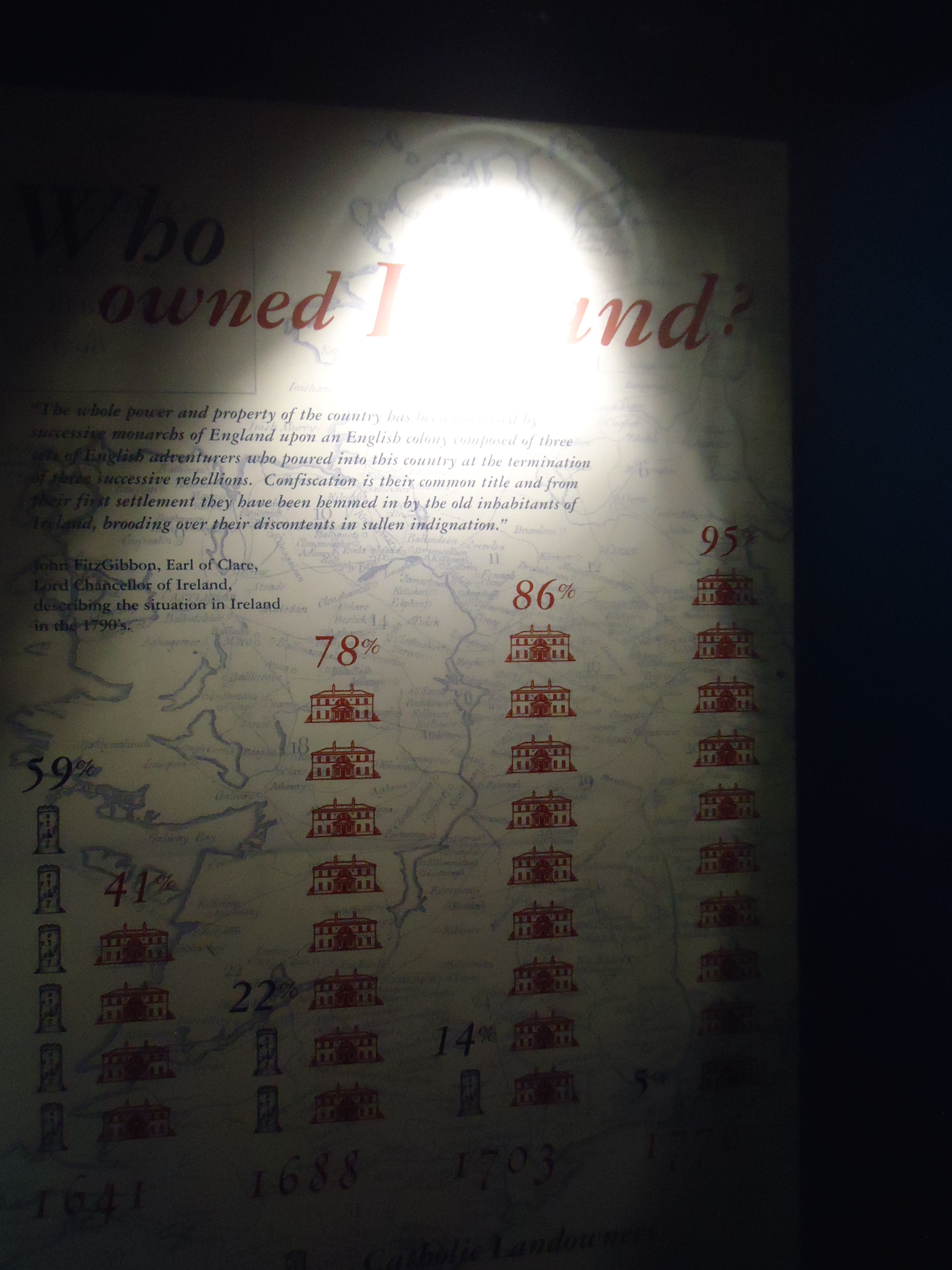

The guy at the door told me I would go into a series of rooms and a recording would come on in each room. He said one room would be dark--I was to wait a bit and a video would come on. So off I went. Each room was poorly lit so, as an invisible narrator told of how the American and French revolutions inspired the Irish rebels, my eyes strained to read the displays. I think this one shows that the percentage of Irish land owned by Protesants grew from 22% to 95% over, say, 200 years.

Some of the rooms had very real looking mannequins that gave me the willies. When I walked up a ramp into the aforementioned dark room, I was horrified to see maybe 15 or 20 very real looking mannequins in various stages of dying. Some impaled on pikes, some slumped over rails. As I walk up the ramp into this amphitheatre of death, the double doors on the far side slammed shut. The lights went out then strobe lights came on and loud gunshots rang out. And screaming. And video screens came to life in various parts of the room with armies charging. I was in between one screen on my left showing a soldier and another on my right showing a boy and watched as the soldier shot the boy in the stomach. It was a surround-sound experience with darkness alternating with flashing lights.

I was appalled and angry that the guy at the door gave me no warning that I would be shut into a dark room to have a virtual experience of war. I think a bit more of a warning was in order. I left longing for the National Trust, which would never pull such a stunt. The irony is, I was so shaken when I left “Vinegar Hill,” that I didn’t read the placards in the next room, which contained the information I came there seeking. What happened on Vinegar Hill? There was very little info at the hill itself, so I had hoped to learn more at this museum cum horror show.

I left literally shaking. A few blocks later, I saw a sign for "River Slaney View." I got out of the car and went to the three benches, hoping for a peaceful pastoral view to restore my equilibrium. Here’s what I saw:

At the bottom of a hill in front of the benches there were train tracks with a children’s play park on the far side. Somewhere beyond the park was the river. WTF? One of my weaknesses is making comparisons that are unfair. Why can’t Ireland have its act together like the UK, curator of National Trust treasures, producer of nature programs such as Planet Earth and Country File--where rural life is celebrated? I decided that the UK had plundered the economies of other countries, Ireland included, for centuries, giving it a clear funding advantage over its former colonies. But the combination of the Enniscorthy Castle spectacle, the “Vinegar Hill experience,” and the non-view of the River Slaney was too much. I got in my car and put on piano music to calm my nerves and headed to Wexford. It was Christmas music, but I didn’t care.

On the way home, I took a photo of a barley field. I am in love with barley fields. The colour is hard to describe. It glows--somewhere between gold and blond. As wind breathes across it, it moves in the most hypnotic fashion. I just loved looking at it. I turned up a country road to get this photo and this was across the street:

Reminders everywhere of “The Insurrection of 1798.”

David, by the way, is enjoying his daily plein air experiences. But tonight he had to listen to my diatribes about museum curators who get their rocks off on scaring people to death. I saw Mr. “You’ll see a video in a dark room” as I left and I really wanted to give him a piece of my mind, however I had no pieces to spare at that moment.

7-30